Sanctifying time

by ENZO BIANCHI

“Be holy”, then, means “be different”, be capable of avoiding the daily idolatrous seduction, that what impeded seeing beyond, be capable of being “other”

There are seasons in which the normal succession of years becomes colored with unprecedented accents, thus causing us to rediscover the novelty that can dwell in even the most ordinary of days. [...] Even, and perhaps above all, in non-religious circles attention was given to dates, anniversaries, memories, festivities. In this, Christianity, which from its very origins rooted in that wise architecture of time that is the history of salvation already narrated in the Old Testament and celebrated in Jewish feasts, has always been careful to see the flow of time not as a cyclic succession of events and seasons, but as renewed opportunity for the irruption of the eternal in history.

In Jesus Christ, the Word of God become man, time has become a dimension present in God, the living and eternal God; time, has become totally sanctified. Now, what does “sanctifying time” mean? God, even before addressing to Israel the invitation “be holy, because I, the Lord your God, am holy” (Lv 19, 2), already “in the beginning” of his creating work, at the completion of the work of six days, “called”, made time holy by making one day, the Sabbath, an “other” day. It is written in fact, “God blessed the seventh day and made it holy” (Gn 2, 3). This, the rabbis comment, occurred to remind us that the sanctification of time is possible above all because of the Creator’s intention and that man’s sanctification begins with rendering time holy, different.

“Be holy”, then, means “be different”, be capable of avoiding the daily idolatrous seduction, that what impeded seeing beyond, be capable of being “other”, of hearing what cannot be recounted, of believing what cannot be spelled out. Consequently, “to sanctify time” means living differently, living that time according to the intention willed by God; above all, it means affirming that not only is there a day that stands at the end of time, but that the end, the goal of time is this: to live in communion with God. Time, therefore, has a precise meaning, because the seventh day is man’s destiny and the destiny of all creation: eschatological anticipation for all humanity, the seventh day is liturgy of all history, transfiguration of the entire cosmos. In God’s intention the believer’s time is a time of rhythms, a time that is different and holy: marked every week by a holy day, the Sabbath, by a holy year every week of years, the sabbatical year, by a holy year every seven weeks of years, the jubilee.

In this way God wanted to impede relegating holiness, mean’s being “other”, to an inaccessible, mythical space. This is the profound meaning of Christian feasts and, around them, of the simple flow of the liturgical year: from Advent, which transforms the memory of the Lord’s coming in the flesh into an invocation of his return in glory, to Christmastide, in which this presence of God among men becomes “epiphany”, a manifestation that culminates in the Trinitarian movement over the rivers of the river Jordan; from the forty days of Lent, in which Christians are invited to be converted to their Lord, returning to him in the simple gestures of every day, such as eating, speaking, struggling, sharing…, up to Passion week, which leads into the vigil that is the mother of all vigils, the holy Night of the Resurrection; from the forty days that follow, which lead to the Ascension, up to the fulfillment of Easter in the effusion of the Spirit on the morning of Pentecost and to the following celebration of the communion of Trinitarian love.

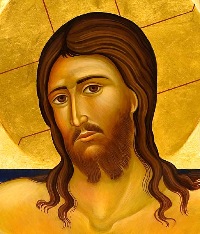

Around these mysteries of our salvation, illuminated by the light of the Risen Lord and awaiting the transfiguration of every creature, we meet again the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, those who in their lives united the Old and the New Alliance, we meet Peter and Paul, apostles from Jerusalem up to the extreme ends of the earth, and all the saints, living recollections of the good news of Jesus’ Gospel.

Thus, formed to faith by these liturgical mysteries, guided by hand by this cloud of witnesses, we arrive in peace and in abandonment to the Lord’s mercy at discovering our humble roots, our not being better than our fathers, our serene returning to the earth from which we were taken and which we have so much loved. These pages wish to be only a viaticum in the long crossing of our life, scanned by the rhythm of the year’s days and months, a series of “places” in which to make a stopover to think about ourselves, the meaning of our own existence, the gift of those around us, so as to be able then to go on, full of gratitude and of trust towards the only “place” capable of slaking our thirst: the very face of God.

Enzo Bianchi

{link_prodotto:id=320}