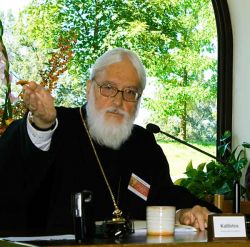

Lecture by Metropolitan Kallistos of Diokleia

The beauty that is the world’s salvation is indeed the uncreated beauty that shines forth on Tabor

The transfiguration of Christ

and the suffering of the world

1. The challenge of Ivan Karamazov.

Let us begin this afternoon with the question that Ivan Karamazov puts to his brother Alyosha in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s masterwork The Brothers Karamazov. “Suppose,” says Ivan, “that you are creating the fabric of human destiny, with the object of making people happy at last and giving them peace and rest, but that in order to do this it is necessary to torture a single tiny baby… and to found your building on its tears. Would you agree to undertake the building on that condition?”. To this Aloysha replies: “No, I wouldn’t.”

If we wouldn’t agree to do this, then why apparently has God done so? How are we to reconcile the tragic mystery of innocent suffering, present everywhere in the world around us, with our faith in a God of love? What, then, is to be our response to Ivan Karamazov?

You will note that, bearing in mind the distinction made by Gabriel Marcel, among others, I spoke just now about the “mystery” rather than the “problem” of evil and innocent suffering. A problem is an intellectual puzzle, a conundrum, which can be deciphered through clear thinking and logical acumen. But evil and innocent suffering, as a mystery, cannot be explained simply through rational argumentation. A mystery is something that has to be changed by action in order for it to become transparent to thought; something that can be resolved, if at all, only through personal experience, personal participation and compassion. We cannot begin to understand suffering unless we are directly involved in it.

Such precisely is the meaning of the crucifixion: God in Christ is victorious over evil because in His own person He suffers to the full all its consequences, without any reservation whatsoever. Vincit qui patitur. Our God is an involved God: “Having loved His own who were in the world, He loved them to the utmost” (John 13:1).

Approaching this mystery of suffering and evil, seeking to add to Alyosha’s brief and enigmatic reply, let us recall the words found in another of Dostoevsky’s novels, The Idiot: “Beauty will save the world.” We shall not begin to understand suffering without being involved in it; but we are not to allow such involvement to make us forget the presence, within this fallen world, of divine and saving Beauty. What, then, does beauty tell us about the salvation of the world? Are Dostoevsky’s words simply escapist? When we watch a child in Africa dying of starvation, or see a hostage tortured and shot in Iraq, what sense does it make to speak of “beauty”? Or has Dostoevsky offered us a vital clue?

The supreme occasion on which the divine Beauty has been revealed to humankind is the transfiguration of Christ on mount Tabor. As the Orthodox Church affirms in one of the hymns at Vespers for the feast:

Transfigured today upon Mount Tabor before the disciples,

In His own person He showed them human nature

Arrayed in the original beauty of the image.

What light, then, is shed upon the mystery of suffering by the divine beauty of the Christ transfigured? What kind of connection is there between the glory of Mount Tabor and the world’s anguish and despair?